Biographical Note

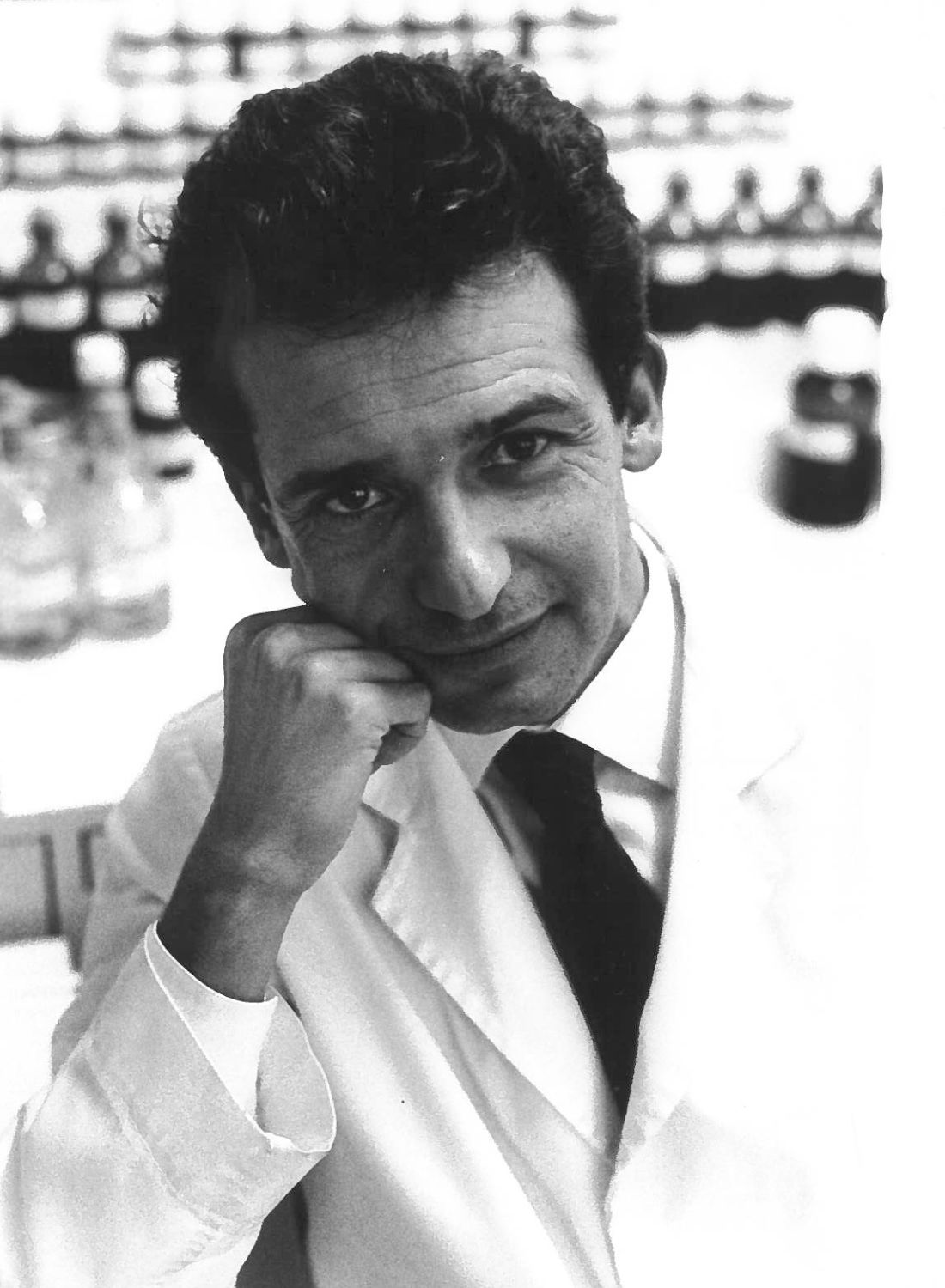

Ernesto Ventós (Barcelona, 1945-2020), who lost his hearing at an early age, began to acquire his great knowledge of perfume when he was a boy, first from his father and later in Grasse (France) and Switzerland as an assistant to perfumer Arturo Jordi. He then joined the family essence and extract distillation firm, founded by his grandfather in 1916, which subsequently evolved into two companies: Ventós, S.A., which markets raw materials, and LUCTA, S.A., which manufactures fragrances, aromas and additives for animal nutrition, with a major presence on the international market.

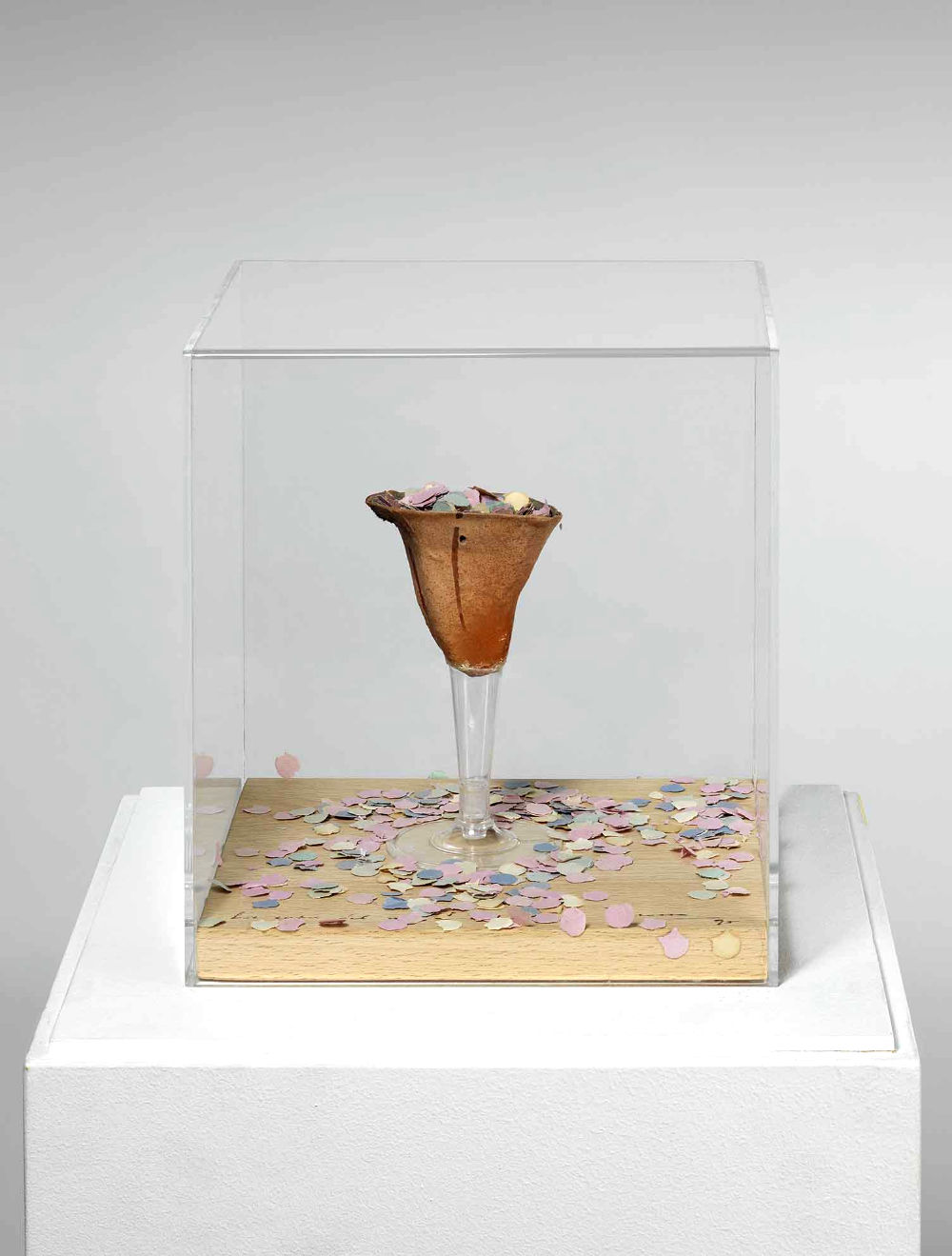

Parallel to his professional career, his participation together with other perfumers in the Olfactory Suggestions exhibition at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona in 1978, sowed the seeds of what would become the olorVISUAL collection: an art collection that includes all the works for the olfactory memories they evoked for the collector.

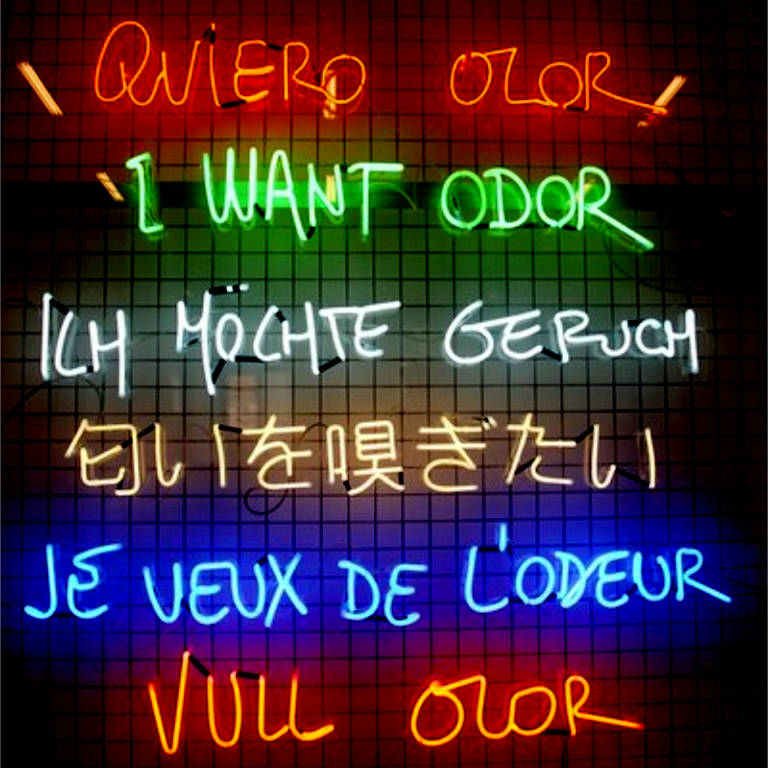

Ernesto Ventós was a far from typical collector, because he wanted to go beyond merely acquiring artworks he liked. Every piece he brought into his collection did something more, because what really fired his enthusiasm was finding works of visual art which stimulated his olfactory memory – works he then gathered together in a collection with a truly descriptive name: olorVISUAL – VISUAL smell.

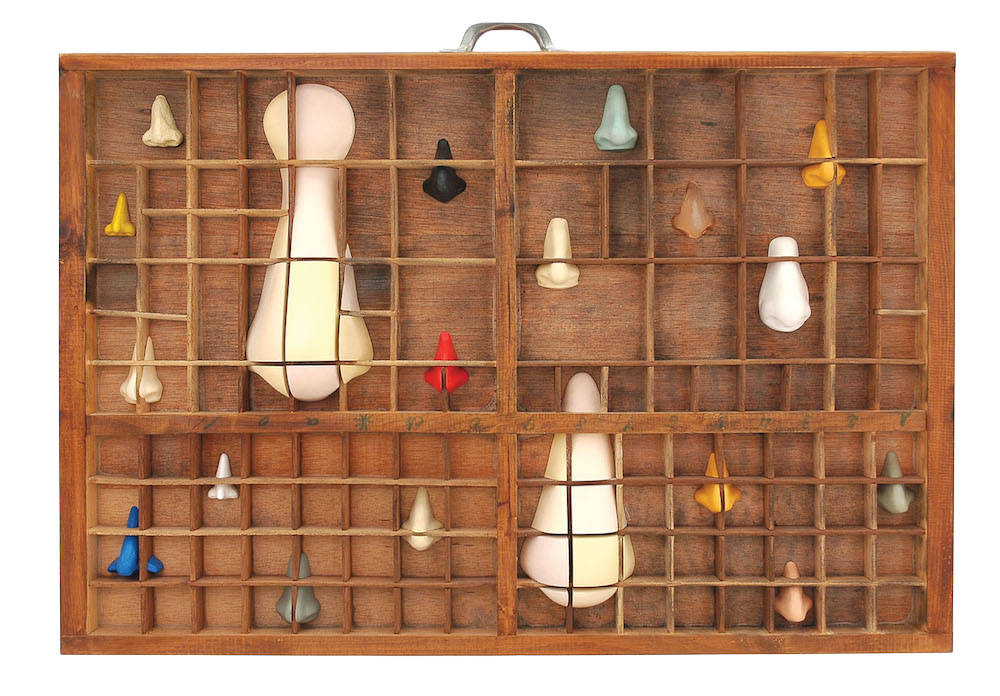

Ernesto’s work and his personal taste and interests were decisive in his choices, because this highly respected perfumer and business executive had a real passion for art, and not only as a connoisseur. He always set aside the time and space he needed to create his own visual artworks, which he exhibited under the name of NASEVO (combining NAS, the word for ‘nose’ in Catalan, and EVO, the initials of his full name). The sense of smell was a vital presence in Ernesto’s daily life, and it is only natural that he should have made the championing of this undervalued sense a personal mission.

As Ernesto explained on many occasions, he was struck by the extent to which visual artists privilege the senses of sight and hearing, and to a lesser extent touch, while neglecting smell. This led him in the late 70s to launch his particular crusade to put this sense on a par with the others, at least artistically, and at the same time to invite us, by way of art, to learn to smell, to educate our most forgotten faculty, which he considered to be the ‘king’ of the senses. And he did this by involving the artists who were to become his allies in this daring venture, this mission to raise our awareness of the sense of smell.